The Left Hand of Darkness at Fifty

By Charlie Jane Anders

When I first read The Left Hand of Darkness, it struck me as a guidebook to a place I desperately wanted to visit but had never known how to reach. This novel showed me a reality where storytelling could help me question the ideas about gender and sexuality that had been handed down to all of us, take-it-or-leave-it style, from childhood. But also, Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic novel felt like an invitation to a different kind of storytelling, one based on understanding the inner workings of societies as well as individual people.

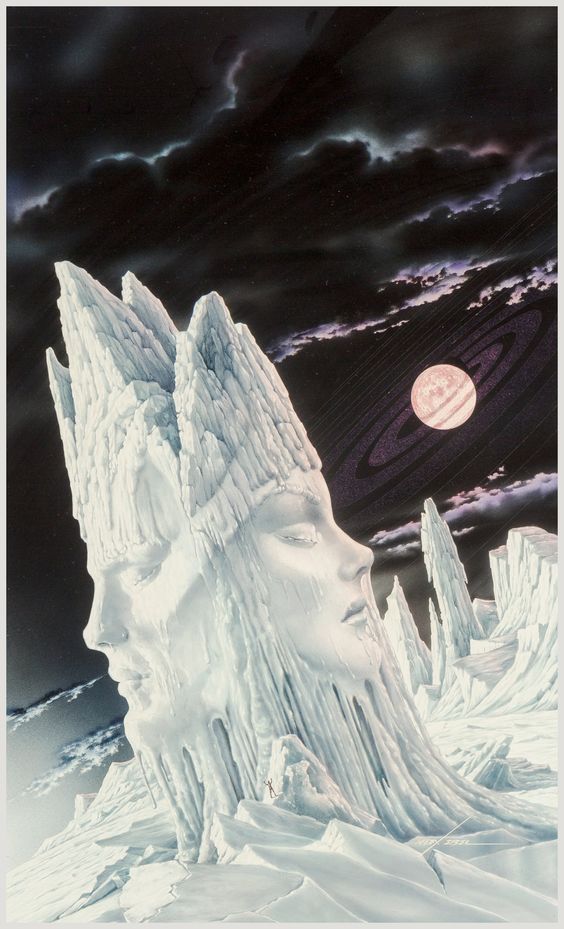

Of course, The Left Hand of Darkness is literally a guidebook to the fictional world of Gethen, also known as Winter. The book takes the form of a travelogue, roaming around the nations of Karhide and Orgoreyn. And by the time you finish reading, you might actually feel like you’ve been to these places, to the point where you kind of know what their food tastes like and how the people act. But for me, and for a lot of other people, The Left Hand of Darkness also left us with a map that leads to another way of telling stories.

I’ve read The Left Hand of Darkness a few times, and each time I come away with a new piece of that map. Le Guin’s writing still surprises me every time. In particular, I’m startled over and over by all the strange details and beautiful quirks she packs into descriptions of her made-up world. I’m also startled by the warmth and generosity of The Left Hand of Darkness, considering how bleak and brutal the actual story is. Somehow, in the midst of a horrifying ordeal, Le Guin finds an incredible sweetness.

The book’s protagonist, Genly Ai, faces many challenges in his mission to the frigid world of Gethen, but the biggest is his struggle to understand a society of people who are gender-neutral most of the time, except for once a month when they go into kemmer and become either male or female. In the hands of an ordinary writer, this “ambisexual” approach to gender would be an interesting what-if. But Le Guin goes much further, building an entire world that feels so rich and undeniable that kemmer, and everything that goes with it, comes to seem like an actual feature of a society that exists. She does this with a million lovely details and a lively, chatty tone, but also by including lots of Gethenian folklore and sayings, which weave together into something that feels bigger than just one novel.

The Left Hand of Darkness was published fifty years ago, but still packs as much power as it did in 1969. Maybe even more so, because now more than ever we need its core story of two people learning to understand each other in spite of cultural barriers and sexual stereotypes. Genly Ai doesn’t trust his main ally on Gethen, a native named Therem Harth rem ir Estraven, and the two of them continually fail to communicate, even as things get worse and worse for both of them. Le Guin captures perfectly the pitfalls of communicating across cultures: the way people talk past each other and pick up on meanings that the other person didn’t intend.

Genly and Estraven’s shared journey is what gives this book its emotional arc, and also its brightness in spite of all the misery in the actual story. The novel’s title comes from a Gethenian proverb about light and dark existing together, which Genly relates back to the yin-yang symbol of Taoism. And it’s true that the darker the events in this book turn, the brighter its spark of hope and friendship becomes.

Even beyond the uplifting story of Genly and Estraven building a friendship, the book is suffused with an optimism that feels especially brave in 2019. We’re never given cause to doubt that the Ekumen is an enlightened society. Or that everyone can make the rough, messy journey from ignorance to awareness. Or that sharing knowledge among different cultures will lead to the advancement of science. Or that spirituality and scientific curiosity can go hand in hand.

While Genly Ai spends the novel learning to see past his own prejudices, Estraven’s story is all about just how far someone will go to create a better future for their people. All of Estraven’s sacrifices are driven by his determination to bring progress and enlightenment to Gethen.

But the highest praise I can give The Left Hand of Darkness is that Le Guin captures the texture of life. This book is full of little moments, bits of sensation and emotion, that show what it feels like to be alive, day after day. Something about the kindness and curiosity in her voice gives substance to all the breadapples and roast blackfish and hot showers and frozen trucks in this book: all the little pleasures and discomforts, the endless struggle and occasional relief of living.

And this is especially true during the long sequence where Genly and Estraven trek across the Gobrin Ice, the frozen waste to the north of Orgoreyn and Karhide. Every inch of their journey is beautifully described, with phrases like “mincing along like a cat on eggshells” and “cinders patter, falling with the snow.” These little moments of poetry go hand in hand with the unrelenting grind of hauling a sled, pitching a tent, eating gichy-michy.

Le Guin gets a lot of the vivid details of an ice journey from the firsthand accounts of Antarctic explorers that she studied. Two of her previous novels, Rocannon’s World and City of Illusions, also include lengthy sequences in which the hero travels across a frozen wasteland along with one companion—but in both those books, the trek feels somewhat sketched in. Here, she packs in so much indelible imagery that you feel like you’re risking frostbite right alongside Genly.

Le Guin never lets go of that connection to the low-level stuff, the tiny physical details and emotional shifts that make up so much of our awareness of the world. And that makes the book, in turn, feel brilliantly alive. I think that’s a big part of why this story feels so hopeful and heartfelt, even at its most dismal.

Becoming so immersed in a society without men and women can be a liberating experience for those of us who still live in a world of labels. The biggest lie that society tells us about gender is that the identities we’re assigned at birth are natural, and that anyone who flouts the boy-girl industrial complex is perverse. Which is the same thing that the Gethenians believe about their mostly gender-free existence—even down to calling people who have a fixed gender identity “perverts.”

A huge part of the value of a science-fiction story like The Left Hand of Darkness is that it allows you to imagine that things could be very different. And then, when you come back to the real world, you bring with you the sense that we can choose our own reality, and the world is ours to reshape. Gethen’s vastly different gender landscape feels real enough that it casts a reflection on all the fixed ideas in our own world. Maybe our rigid gender binary is just as made up as their neutral-except-once-a-month gender is. Maybe our government-issued pronouns and official stereotypes don’t have to define us always. Especially for my fellow trans and nonbinary people, a story that undermines the assumptions behind coercive labels feels magical.

When Le Guin wrote this novel, there were plenty of trans people around, but most people knew only about a handful of famous examples, like Christine Jorgensen or Michael Dillon. Nonbinary people didn’t have a widely accepted gender-neutral pronoun (even though some people did use they colloquially for this purpose). There was a hugely popular and controversial musical called Hair, trading on the shock value of men having long hair!

The Left Hand of Darkness draws on a tradition in science fiction of questioning gender norms, the same way science fiction questions everything else. There have been many novels and stories about all-female or female-dominated societies, going back to 1905’s Sultana’s Dream, by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, and 1915’s Herland, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. And in 1960, Theodore Sturgeon had published Venus Plus X, in which the descendants of humanity have become nongendered, with both male and female reproductive organs (and two uteruses per person).

But what makes Gethen’s ambisexual world so striking and memorable is the care Le Guin takes to show how the existence of kemmer changes every other part of the society. We read folktales about star-crossed kemmering, hear about the public kemmerhouses where people can mate freely, and also learn that people must live in big enough communities that there are enough possible pairings for people who are kemmering.

Unresolved sexual tension is a huge motif in The Left Hand of Darkness—it can be a source of power and human closeness, but it can also lead to despair. When we witness the foretellers of the Handdara answering Genly Ai’s question, in the book’s strangest and most delirious scene, a big part of the process turns out to involve a Pervert (someone who’s always male) and one foreteller who happens to be in kemmer. But elsewhere in the book, we witness attempted seductions and unrequited longing, torment and frustration.

In many ways, The Left Hand of Darkness disrupts gender as well as it ever did. But there are some issues, too. Le Guin chooses to use he as a gender-neutral pronoun for the Gethenians, which undercuts the idea that they’re supposed to be neither male nor female. Even when the book was brand new, many feminists complained about this pronoun choice, and Le Guin later wrote that she “couldn’t help but feel that justice was on their side.” In 1975, when Le Guin reprinted a short story that takes place on Gethen called “Winter’s King,” she changed all the pronouns from he to she. But she felt that they was too confusing as a gender-neutral pronoun.

At the same time, some feminists, including the author of The Female Man, Joanna Russ, complained about the fact that we never see child-rearing or other stereotypically female pursuits in this novel, even though every Gethenian is potentially a mother as well as a father. Le Guin made up for this, years later, by writing another short story about Gethenian domestic life, “Coming of Age in Karhide.”

Le Guin’s thought experiment about gender is still rooted in essentialism. Everything about the Gethenians’ gender identities is driven by their biology, and even the Perverts are different only because of a biological happenstance. Even as this book drives you to question all of our assumptions about male and female bodies, it never raises any questions about how gender shapes us independently of our biological sex (the way a lot of science fiction has, in the decades since.) If anything, The Left Hand of Darkness reaffirms the idea that biology determines your gender and sexuality.

But these weaknesses in the book’s approach to gender are also strengths, because they help us to understand what’s wrong with the book’s severely flawed narrator, Genly Ai. Genly Ai is a misogynist. This becomes more apparent to me every time I reread The Left Hand of Darkness, and it’s the main reason why Genly is bad at his job.

Le Guin makes this very apparent early on in the book, and keeps giving us little hints thereafter. Anytime Genly notices any traits that he considers feminine in the Gethenians, he’s disgusted. Especially when he talks to Estraven, who’s actually trying to open up to him, Genly sees these attempts to communicate as “womanly” and thus lacking in substance. The only person in the book who gets a female job title is Genly’s “landlady,” who’s mocked for her overly feminine “prying” and for having a fat ass. Even King Argaven, who comes across as high-strung and paranoid, is described as having a shrill laugh (shrill being one of those words that’s always used to describe women who speak up too much).

Much later in the novel, Genly informs Estraven that in the Ekumen, women seldom seem to become mathematicians, musical composers, inventors, or abstract thinkers. “But it isn’t that they’re stupid,” Genly adds, digging himself in deeper. (He doesn’t include “science-fiction writers” in that list, but in 1969, most people would have. That same year, Le Guin herself was forced to use the byline U. K. Le Guin for a story published in Playboy, so readers wouldn’t know that she was a woman.)

It’s not just that Genly Ai is incapable of seeing Estraven as both man and woman—it’s that any hint of femaleness revolts him, especially in people who are supposed to be powerful. Genly can’t respect anyone whom he sees as having female qualities, and thus he recoils from Estraven, the one person who tries to be honest with him. And Genly’s character arc is about getting over his hang-ups about women and his macho pride, every bit as much as learning to understand his friend.

It’s fascinating, and very realistic, that Genly Ai is an enlightened representative of an advanced, harmonious culture—while also being a deeply messed-up individual who cannot see past his own limited ideas about gender and sexuality. He’s curious and open-minded about everything, except for the huge areas where his mind has been long since closed. He doesn’t even glimpse all the things that his privilege has allowed him to avoid looking at.

In this context, the use of the male pronoun for the Gethenians feels like an extension of Genly Ai’s own issues. And his slow progress toward opening his mind is part of one of the main overarching preoccupations of The Left Hand of Darkness: the attainment of wisdom.

The Left Hand of Darkness is full of those beautiful observations of snow and food and daily life, as well as stories and sayings and little touches that illuminate the societies of Karhide and Orgoreyn. But another reason this novel shines so brilliantly is all of the philosophical and mystical dialogues that are embedded within it. So many of the discussions in this book are endlessly quotable, like the explanation of why “to oppose something is to maintain it.”

You can’t separate the politics of this novel from its spirituality. People are constantly grappling with big questions about what makes a group of people into a nation, and the meaning of patriotism, alongside discussions of the balance of light and darkness (borrowed liberally from Taoism) and Gethenian cultural concepts like shifgrethor.

Gethen is a world without war—which may be due to its harsh climate, or to its lack of men—but it’s also just beginning to develop the concept of the nation-state. Orgoreyn, with its oppressive bureaucracy and lethal secret police, is closer to nationhood than Karhide, but a territorial dispute is pushing both countries closer to patriotic fervor. (And we’re reminded, over and over, that patriotism is based on fear more than love.)

Part of what Genly Ai offers to the people of Gethen is the hope that they could leapfrog over this drive toward nationalism by joining the Ekumen and becoming one unified world among many. One of the most striking moments in the story comes early on, when Genly shows King Argaven his ansible (a device that can communicate instantaneously across the galaxy). For a moment this petty ruler of one kingdom is connected to a huge cosmic backdrop. And of course, their attempt to communicate is largely a failure. The Ekumen remains in the background, something we glimpse in the distance even as the story stays small and local. (And the story of a “more civilized” person visiting a less advanced society manages to be less problematic than it could have been, because Genly tries to learn from the Gethenians, and doesn’t bring more people or technology to them until they are ready to receive it.)

And the Ekumen are just one of the things in the book that we glimpse, which feel important but too big to see clearly. The nature of prophecy in this book is the same way—we visit the foretellers and see them at work, but we don’t really understand how it works, and the future remains huge and unknowable even after they speak. And of course, when prophecy falters, it’s always due to communication failure, because someone asked the wrong question or misunderstood the answer. Also tantalizing: the story of Meshe, who was a Weaver in a foretelling where someone asked for the meaning of life, and it all went horribly wrong. Afterward, Meshe became a mystical figure who could see all of time, who still has worshippers over two thousand years later.

The Gethenian concept of shifgrethor, too, feels huge and difficult to understand, even after we get an explanation. It’s got elements of status, or prestige, but it’s more than that, and our best hints about it come from some of those fables that are sprinkled throughout the text, including the story of Getheren of Shath. This, along with other linguistic concepts like the untranslatable nusuth, feels like a nod to the famous Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that language shapes the way we think. (Edward Sapir, who helped develop that theory, worked with Le Guin’s father, the anthropologist Theodora Kroeber, and also helped translate for Ishi, the lone survivor of the Yahi tribe whom Kroeber befriended and studied.)

So this book is full of contrasts between the intimate, human-size world and the unseeable hugeness in the distance. (Much like the enormity of the Gobrin Ice, with the Esherhoth Crags looming on the horizon.) In fact, you could almost say that the people in this novel are operating in the shadows of these massive background objects, in keeping with this book’s preoccupation with shadows.

The Left Hand of Darkness surprises me again every time I reread it. There are so many wonderful ideas and stark emotional moments, and Le Guin’s language always startles me with its sheer power and wonder. And every detail in the book has little stories embedded inside it, and these stories keep intersecting and building on each other every time I revisit them—until you start to realize that everything is made of stories. As Genly Ai says on the very first page, “Truth is a matter of the imagination.”

Gender, sex, romance, desire, power, nationalism, oppression—they’re all just stories we tell ourselves. And we can tell different stories if we choose.

From Charlie Jane Anders’s afterword to The Left Hand of Darkness: 50th Anniversary Edition, by Ursula K. Le Guin, published this week by Ace, a division of Penguin Random House.