Feminist Futures in Science Fiction

by Margaretta Jolly

Science fiction has often been seen as a masculine genre, yet it has also attracted feminists who find in it a means to survey speculative futures in which gender relations can be played with, exaggerated, tested out or transformed. Margaretta Jolly explores the worlds reimagined by women science fiction writers.

Imagine a world in which everyone is ‘five-sixths of the time hermaphrodite neuters’, but whose gender emerges each month, according to a fertility cycle, alongside a system of temporary partnering. That is the scenario in Ursula Le Guin’s marvellously strange – and gloomy – Left Hand of Darkness (1969), set in a future ice-cold planet in which an envoy from a warmer earth must try to find a way to relate.

Or consider the unhappy lot of humanoid boys being sacrificed to incubate the offspring of giant intelligent – and otherwise caring – centipedes. Olivia Butler’s story in Bloodchild (1984) was part of an extraordinary oeuvre in which she explored race and gender relationships in trans-species plots.

And what about the scene in Zoë Fairbairns’ 1979 novel Benefits, the UK’s answer to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985)? In its eugenicist future state, a woman prime minister uses welfare benefits to force women back into the nuclear family to reproduce, while a lesbian-led feminist resistance argues over how to fight back.

Such fiction takes classic sci-fi scenarios but twists and turns them in refreshing directions. For example, feminists emphasise that care-work is just as important as other forms of labour in shaping a society. For this reason, many plots focus on the struggle for reproductive choices and reimagine domestic arrangements. This interest can be seen in the very first true sci-fi novel, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818).

This tragic tale of what happens when the machine becomes master over its human designer, has inspired artists since its publication. But we can also see it as a meditation on what any mother feels in giving birth to a being over which one has responsibility but not full control.

Bengali Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain's 1905 utopian short story Sultana's Dream is another pioneer here. In ‘Ladyland’ men are confined indoors, while women, under new laws which prevent early marriage and ensure girls’ education, reinvent a peaceful, clean civilisation using solar power and ingenious weather control.

Ten years later, American Charlotte Perkin Gilman’s 1915 Herland also proposes a non-violent (and vegetarian!) future; men having died out 2,000 years previously, women reproduce by parthenogenesis, sharing all childcare collectively.[1]

How have feminist science fiction writers responded to politics?

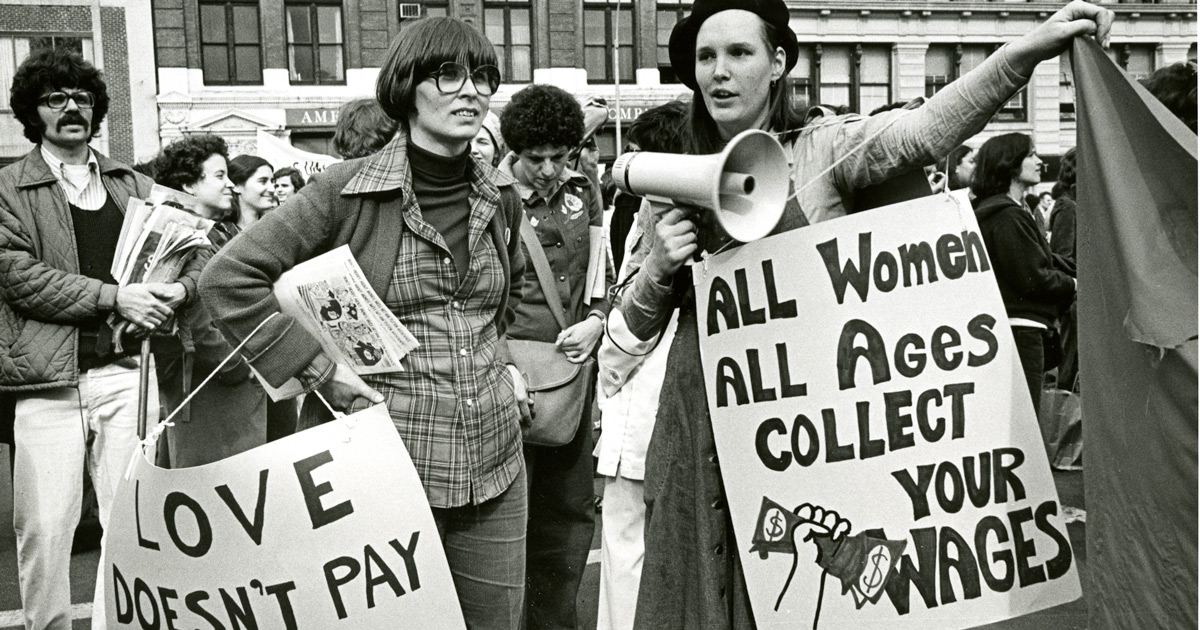

During the so-called ‘second wave’ of feminism and civil rights in the 1960s–80s, science fiction solutions became more diverse and complicated. Fairbairns explains that her novel Benefits was inspired by the 1970s Women’s Liberation Movement debate over whether housework should be paid for by the state. She felt that ‘there were very convincing arguments on both sides’:

Clearly women whose work is the work of raising children … is as valid a job of work as any other and why should they have to pay for doing that by being financially dependent on men? I totally supported that. But I could also see that if the state started giving women money to look after kids, it would be used as a way of control. So I was in two minds about this, and being in two minds is a good position for writing a novel.[2]

Related to such literary debates are experiments with sexual relations and identities. A rise in pornographic sci-fi in the 1960s produced the offensive clichés which Joanna Russ amusingly treats as ‘The Weird-Ways_of_Getting_Pregnant’ stories or, conversely, the duplicitous seductress-robot. Lesbian-centred feminist sci-fi offered egalitarian alternatives but, as a group of contributors to the Women’s Press anthology Despatches from the Frontiers of the Female Mind discussed in 1985, this could pose other aesthetic challenges.[3]

A different warning comes from Tanith Lee’s Don’t Bite the Sun (1976) and Drinking Sapphire Wine (1977), where a robot class doing all the work leads to a dull, dissolute and not entirely gender-liberated life for the endlessly reborn and promiscuous hippy humans in the space colonies. Today’s similarly confusing challenges in a sexually liberated yet also neo-Puritan West, are confronted in Naomi Alderman’s 2016 The Power. This thriller explores what happens when women can electrocute people by touching, create their own doctrinal ideology and even learn how to rape.

Feminists have also used the trope of the space-quest to protest women’s historical position as 'she who stays behind and waits'. Scottish novelist Naomi Mitchison, for example, in Memoirs of a Spacewoman (1962), has her heroine Mary (an expert communicator with alien intelligences), suffer time blackouts, during which she keeps returning to a changed world. This challenges her recurring desire to bear children. But she is a brilliant inter-stellar linguist who loves her job – so why shouldn’t she be able to both work and mother?[4] A more recent reboot is neuroscience graduate Temi Oh’s Do You Dream of Terra-Two? (2019), which unravels the relationships between six British teenagers selected for a mission to an earth-like world outside the solar system involving 23 years confined on a spaceship. American Ann Leckie also offers a contemporary twist in space operas which feature transgender or gender-blind warriors, animated artificial consciousness and manipulative gods.

How has feminist science fiction grappled with environmental crises?

The epic dimensions of sci-fi pitch often survival at species-level and many feminists have engaged with themes of population control and environmental catastrophe. These have contemporary urgency, and we can feel the poignancy of earlier imaginings such as Rose Macauley’s What Not, written just as the First World War was ending in 1918. In what Macauley termed a ‘Prophetic Comedy’, an autocratic government is trying to lay the grounds for long-term peace by dividing the population between those with or without brains, to prevent the birth of more people stupid enough to pursue conflict. Kitty, ranked as A in the intelligence spectrum, falls in love with the ‘uncertified’ Minister of Brains, naturally showing the inadvisability of this strategy.

A more utopian solution is Octavia Butler’s 1993 Parable of the Sower, where humans learn to care for each other and the planets through ‘Earthseed’, a new religion based on the principle that ‘God is change’. This vision evolves from the African-American heroine’s inheritance of the condition of ‘hyperempathy’, when she feels others’ pain as if it were her own and bleeds if they bleed. Such questions of whether we can collectively develop enough empathy, including with non-human species and the earth itself, could not be more pertinent.

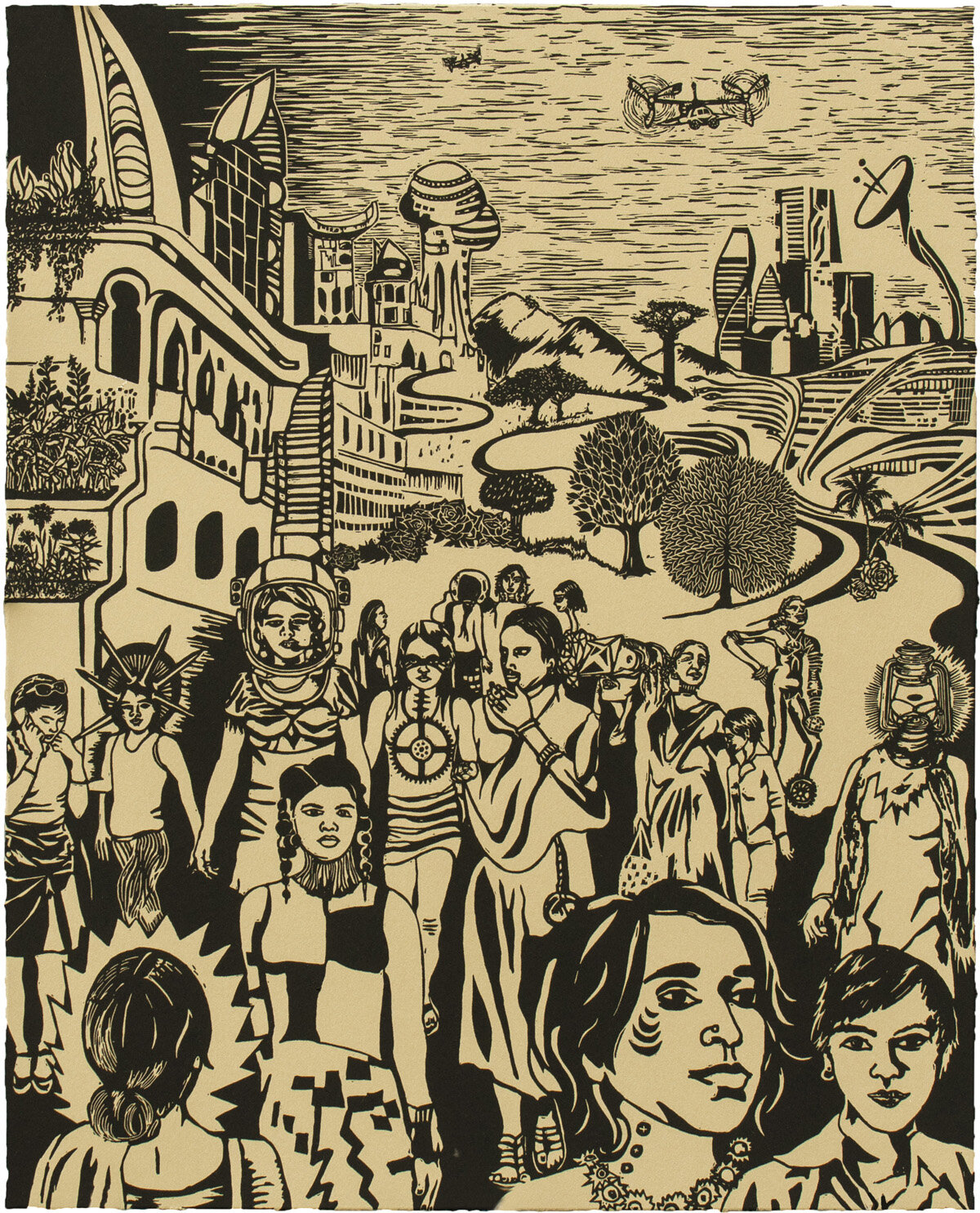

How does science fiction engage with feminist ideals?

Because sci-fi looks towards the future, it can take feminist arguments in a different direction from realist or historical fiction and interrogate what an ideal feminist society might look like. Admittedly, this can be as obvious and heavy-handed as sexist approaches – Joanna Russ wryly identifies this as the ‘The Noble Separatist Story’. But at its best, it produces intriguing thought-experiments and rollicking adventure stories.

It can also allow us to stretch feminist views on science. Donna Haraway’s ‘The Cyborg Manifesto’ of 1985 put this in theoretical terms, where she argued that feminists should be wary of romanticising a mythical matriarchal past or identity. ‘I’d rather be a cyborg than a goddess’, she concluded, urging feminists to embrace technology and recognise biology to be dependent upon it. A trans-feminist approach might be considered compatible with this, imaged in Susan Stryker’s provocative reclaiming of herself as a Frankenstinian monster, in a world of everyday cosmetic surgery and hormonal treatments.

Certainly, sci-fi shows us that gender harmony and liberation involve transcending simplistic biological determinism. But, as we come to understand biology as itself both changeable and profound, so a feminist future must also engage respectfully and carefully with it. Corporate company perks of egg-freezing; ageist transhumanism; bio-terrorism and surveillance; sex algorithms and racially cleansed robot carers: these arguably show a dystopian future becoming our present.

How can science fiction engage with race?

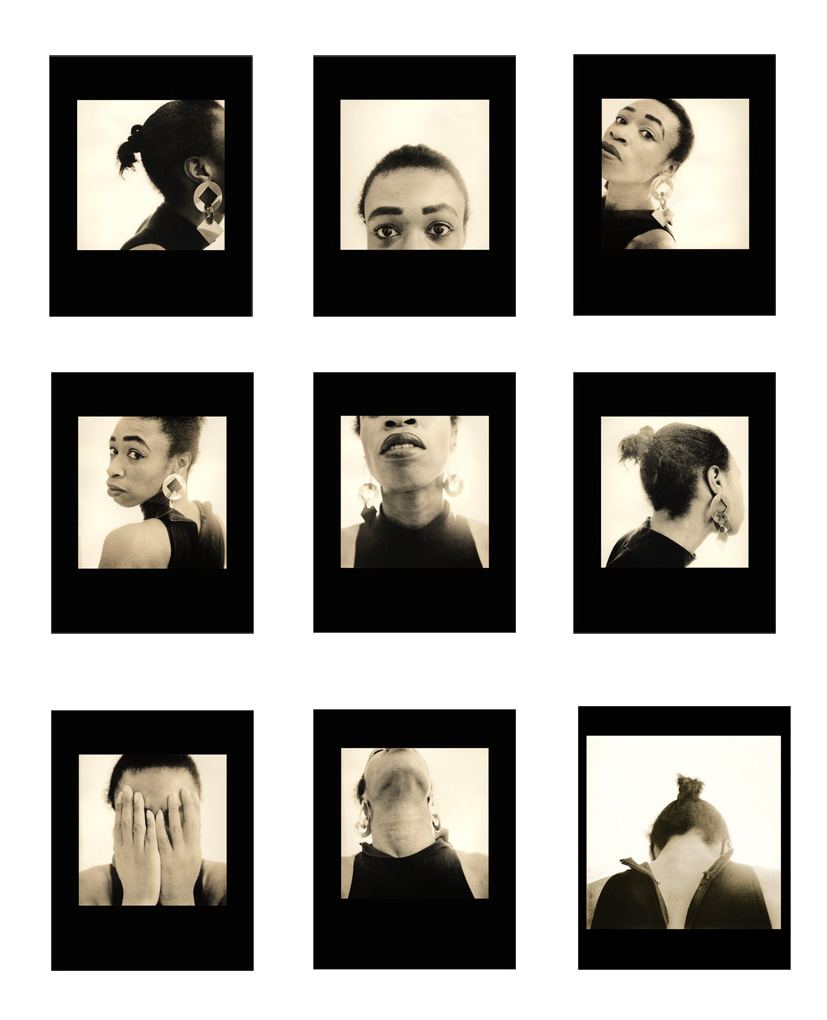

Afrofuturists have also found sci-fi’s futurist orientation useful to combat a backwards-facing nostalgia, yet without endorsing all it brings. This concept has been associated with avant-garde African American music, a legacy revived by musician Janelle Monáe. In the UK, Cultural Studies theorist Stuart Hall made the same move, stating he was tired of art which imprisoned those of African heritage in a ‘primitivist’ mode: 'I will not be shut out of future history because of what has happened in the past', he explained in his 2012 oral history.[5] He praises Joy Gregory’s ‘autoportraits’ as an example of art in which there is no obvious futurism, but rather a subtle break from historical literalism alongside a claim to equal rights of representation.

In literature, a wave of African-influenced sci-fi writers are taking Afrofuturism to the next stage. The African Speculative Fiction Society recognised two feminist writers in its 2019 awards, Akwaeke Emezi: whose Freshwater tells of a young Nigerian woman whose mental illness is in fact an otherworldly split consciousness, and Nnedi Okorafor, for her graphic novels about the Black Panther’s techno-genius sister battling for justice in the land of Wakanda.

Sci-fi’s futurism clearly expresses the concerns of the present. And precisely because of this, it is all the more important to appreciate its own history, as it has charted and ciphered the anxieties of each period and constituency. Just as so many sci-fi forms begin from the premise of lost archives being interpreted (or misunderstood) on a future planet, libraries and archivists play their own part in connecting, refracting and rethinking the past towards a – hopefully – better future.

[1] Add MS 88904/1/145: 1980–1998. Recently reissued as a Modern Classic 2015.

[2] Zoë Fairbairns interviewed by Margaretta Jolly, Sisterhood & After: The Women’s Liberation Oral History Project, 2010–2013. British Library Sound & Moving Image Catalogue reference C1420/24, transcript p. 113, track 05

[3] LaFanu, Sarah, Tanith Lee, Lisa Tuttle, Gwyneth Jones and Josephine Saxton, in Conversation (1985). London: Institute of Contemporary Arts/British Library. C95/195

[4] Add MS 88904/1/299 Naomi Mitchison (1897–1999) (1980–1999).

[5] Stuart Hall interviewed by Paul Thompson, Pioneers of Social Research, 2012. British Library Sound & Moving Image Catalogue reference C1416/42, transcript p. 134, track 06.